Pastern dermatitis

Persistent wet, muddy conditions in autumn will often have horse owners dealing with pastern dermatitis, aka mud fever, cracked heel or greasy heel. This stubborn skin infection begins with redness, bumps, pustules and scabs on the back of the pastern and may also affect the inner side of the cannon bone. Muddy winter weather makes conditions ripe for pastern dermatitis, but the actual causes for this ailment are numerous. Read further to learn what factors play a role and what you can do to treat mud fever.

What is it?

Pastern dermatitis, or mud fever, is a catch-all term for a number of skin inflammations which begin in the back of the horse's pastern. Typically, mud fever is most often seen in autumn and spring – seasons in which the horse's organism is under strain due to moulting.

The back of the pastern is a highly stressed body part that is continuously exposed to environmental irritants such as dirt, moisture and bacteria. Many horses are sensitive to this inflamed skin being touched, which makes cleaning and topical treatment all the more difficult. The first signs of pastern dermatitis are redness (sometimes accompanied by itch) and flaky, cracked skin, followed by bald spots with the area taking on a greasy look and scabbing. In extreme cases it can lead to phlegmon with fever.

Chronic cases can cause major, irreversible damage to the tissue and eventually lead to lameness.

Mud fever appears in different forms depending on stage and cause:

- It is most often seen in mild forms with hair loss, dry skin flakes and the beginning of scab formation. The skin at the back of the pastern is red, itchy or painful. At this early stage, the condition can be quickly brought under control.

- In more exudative forms, the inflammation has already spread to the sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Pus-filled blisters form, break open, and harden into thick crusts. The damaged skin is susceptible to secondary bacterial infections, leading to the discharge of pus. In its rarely seen severe form, sections of the skin become necrotic and peel off or decompose into a greasy mass.

- Its most severe, proliferative form is verrucous pododermatitis. Here, a massive thickening of the underlying skin layer (dermis) occurs which begins with calluses and creases to the skin. The skin hardens and cracks open. Excess granulation tissue forms into grape-like growths and can spread over the entire lower leg.

What causes pastern dermatitis?

It wasn't all that long ago that pastern dermatitis was thought to be a hygiene problem and a sign of poor stable management. Many responsible horse owners could not explain its occurrence despite providing optimum care, whilst a horse in the same barn could wade around for hours in a muddy paddock and never be affected.

Today pastern dermatitis is considered to be a multifactorial disease, meaning that it cannot be assigned to one single cause, but rather to the occurrence of several circumstances.

Moisture

Skin needs moisture, but prolonged exposure to water can lead to a number of skin diseases. Sustained exposure to moisture affects the skin's lipid layer, the layer which acts as a barrier against environmental irritants. The topmost layer of skin appears to become more porous. A humid climate can also cause an increase in the skin's pH values. If the skin barrier is impaired, repair processes occur at low pH values; alkaline conditions hinder these processes.

Pastern dermatitis can therefore not only develop from a muddy run or damp bedding, but even from dewy pastures that dry out late, if ever.

Mechanical irritants

Pastern dermatitis can arise from small injuries to the back of the pastern like skin lesions from thistles, grain stubble or itchy insect bites as well as from skin irritations from jagged sand particles used in paddock or manège footing.

Bacterial infections

Bacterial pastern dermatitis originates from an inflammation that is initially confined to the hair follicles and spreads from there. The skin lesions appear as small nodules which are often notices from clumps of bristle-like hair. Here the hair may already be matted with pus and small scabs. Two main types of bacteria are responsible for these inflammatory processes: Staphylococcus aureus and Dermatophilus congolensis.

Staphylococcus bacteria colonise healthy skin and mucous membrane flora and under certain circumstances can become pathogenic agents. With horses, skin injuries or areas stressed by mechanical factors serve as entry points. What makes the treatment of a staphylococcal infection more difficult is the resistance of some strains to antimicrobial agents.

The second bacterial agent associated with pastern dermatitis is Dermatophilus congolensis. Transmission occurs through direct or indirect contact with infected animals or objects. In horses, transmission can occur through cleaning, saddle and bridle equipment used on more than one horse, as hair contaminated with bacterial spores can remain infectious for months, if not years. The bacteria penetrate the skin layer through small skin cracks, such as those caused by moisture or insect bites, and multiply anaerobically. D. congolensis can also be transmitted by ticks. Symptoms of pastern dermatitis are stronger in animals infested by ticks and tend to become chronic. The reason may be that tick infestations lead to a reduced immune response in the organism.

Chorioptic mange mites

Chorioptic mange mites are surface dwelling mites that measure between 0.3 and 0.5 mm and feed on skin cells, sebum and exudate. Chorioptes equi especially affect heavily feathered breeds because they thrive in warm, moist environments. The mites may be transmitted by direct or indirect contact and trigger an immediate hypersensitivity reaction. Horses with leg mites are often itchy and will stamp their feet. Typical signs are eczema with dandruff and scabbing, later hyperkeratosis and wrinkle formation with a tallowy, greasy coating around the back of the pastern on the hindleg; the forelegs are affected less often.

Immunological causes

Vasculitis

Vasculitis is an inflammation of the arteries, veins or capillaries and is often secondary to a variety of diseases. Vascular skin inflammations are often related to immunological events. A hypersensitive reaction that is triggered by, for example, bacteria, viruses, fungi, or even medications, leads to formation and deposit of immune complexes, contributing to vascular deterioration. The skin reacts with redness, secretion and scab formation. Edemas will often form at the affected areas.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is triggered through the combination of an allergen with the body's own proteins. It is typical for individual animals to show mud fever symptoms as allergic reactions to pasture plants or bedding, for example.

Irritant-caused contact dermatitis

Skin inflammations can also be caused by direct and prolonged contact with irritants like faeces and urine, topically applied medications, or plants such as nettles.

Symptoms of contact dermatitis from irritants are similar to those of allergic contact dermatitis and are expressed as redness, edemas, and papules.

Photosensitisation

Mud fever can also be caused by coming into contact with photodynamic substances, either externally or through the digestive tract, where they enter the skin via the vascular system. In combination with absorbed ultraviolet rays, this leads to skin reactions, especially in areas with light, white or little hair. St John's Wort is often cited as a theoretical trigger – in practice, however, this effect has not been proven, because a horse would have to ingest a large quantity of it to bring on a reaction. Medications can also facilitate photosensitisation. Photosensitisation through direct contact is most often seen in horses kept in pastures with a lot of alsike clover (Trifolium hybridum).

Is my horse susceptible to mud fever?

Horses with heavy feathering like Gypsy Cobs, draught horses and some pony breeds suffer more frequently from pastern dermatitis. Genetic factors may also play a role in susceptibility to the disease. Studies show, for example, that horses with mud fever display skin barrier defects similar to those from canine atopic dermatitis in dogs.

Horses with white hair on their pasterns are much more likely to suffer from mud fever. This may be due to stronger absorption of UV rays, influencing the barrier function of the epidermis.

Mud fever also occurs more frequently to the hindlegs. One reason for this is because the shallower angle of the long pastern bone, which comes closer to the ground during landing and thus in more frequent contact with faeces, urine and mud.

How can I combat mud fever?

Alongside topical treatment, look to boosting the horse's natural defences and metabolism. As with many other ailments, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Bacteria and mites have no chance with healthy horses!

Optimise stabling and care:

Mud fever can be brought under control more easily when ground surfaces are clean and dry. The back of the pastern should be kept clean as a preventive measure. Caution: excessive washing can weaken the skin!

Heavy feathering should be carefully clipped or cut with scissors. Be careful not to injure the skin!

Metabolism relief:

The increase in protein intake when switching from hay to pasture grass in the spring can put strain on the horse's metabolism. But a horse's metabolism can undergo massive stress in early winter as well, when it is almost inevitably flooded with pollutants found in hay.

These immense demands put a heavy strain on the body's detoxifying organs, the liver and kidney, which remove some of these substances through the skin. Herbs beneficial to the liver and kidney like milk thistle, nettle, and dandelion can alleviate mud fever and help to prevent inflammatory skin diseases.

Targeted supplementary feeding of zinc and biotin:

We recommend the feeding of nutrients that promote strong and healthy skin, especially during moulting periods.

Boosting the immune system:

A strong immune system will protect your horse from ailments due to environmental irritants. Herbs like echinacea, taiga root, ginseng and rose hips (with vitamins) provide optimum support for the immune system.

Salves to apply to the back of the pastern:

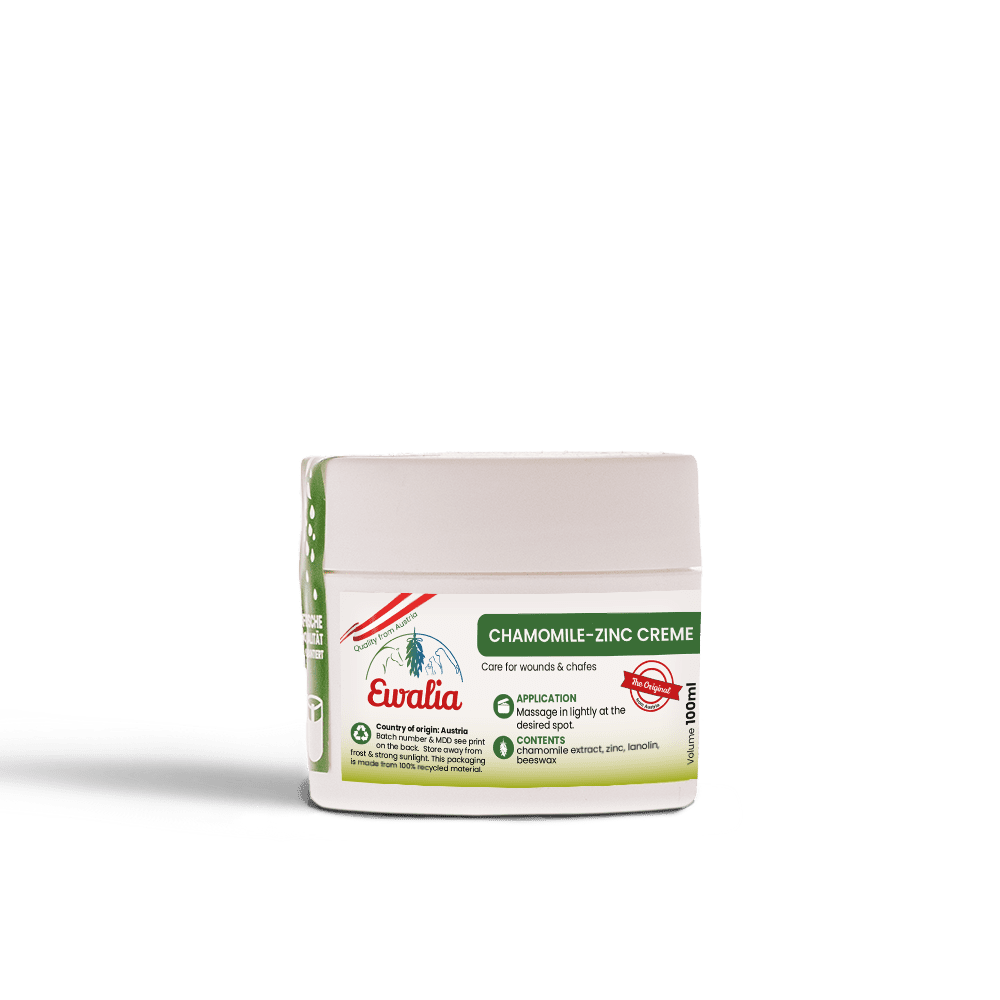

Salves containing cortisone are often recommended to relieve itching and pain, but they weaken the skin's natural defences. Salves made from natural active ingredients will provide more sustainable improvement. Camomile extracts, for example, are soothing to the skin. The essential fatty acids in grape seed oil help to strengthen the skin barrier. Zinc promotes wound healing and skin regeneration. Beeswax as a foundation contains vitamin A which supports cell regeneration and skin elasticity. The wax has a positive effect on wound healing and reduces bacterial inflammation.

Quellen und weiterführende Literatur:

- Brendieck-Worm, C., & Melzig, M. F. (2018). Phytotherapie in der Tiermedizin. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag KG.

- enpevet.de. (18. 10 2012). Von http://www.enpevet.de/Lexicon/ShowArticle.aspx?articleid=41811 abgerufen

- Raizner, N. T. (2017). Untersuchungen zur Mauke des Pferdes. München: Tierärztliche Fakultät.

- thieme.de. (08. 11 2020). Von https://www.thieme.de/de/tiermedizin/mauke-beim-pferd-136223.htm abgerufen

- Van de Hoven, R. (15. 10 2016). vetmeduni.ac.at. Von www.vetmeduni.ac.at/fileadmin/v/z/veranstaltungen/2016/Pferde-Symposium_20161015/Van_den_Hoven_Ekzem.pdf) abgerufen